- Learn more here - https://www.hacksoft.io/blog/django-styleguide-survey - or simply jump to the survey here - https://form.jotform.com/213492755022049.

- The survey takes 5 to 10 minutes to complete.

- We will run the survey for 2 months and a half, until the end of February.

- When the survey is done, 10 participants are going to be picked at random, each of them receiving a $50 Amazon gift card.

Django styleguide that we use in HackSoft.

- We have a

Styleguide-Exampleto show most of the styleguide in an actual project. - You can watch Radoslav Georgiev's Django structure for scale and longevity for the philosophy behind the styleguide.

Table of contents:

- Overview

- Cookie Cutter

- Models

- Services

- APIs & Serializers

- Urls

- Settings

- Errors & Exception Handling

- Testing

- Celery

- Misc

- Inspiration

In Django, business logic should live in:

- Model properties (with some exceptions).

- Model

cleanmethod for additional validations (with some exceptions). - Services - functions, that mostly take care of writing things to the database.

- Selectors - functions, that mostly take care of fetching things from the database.

In Django, business logic should not live in:

- APIs and Views.

- Serializers and Forms.

- Form tags.

- Model

savemethod.

Model properties vs selectors:

- If the property spans multiple relations, it should better be a selector.

- If the property is non-trivial & can easily cause

N + 1queries problem, when serialized, it should better be a selector.

We recommend starting every new project with some kind of cookiecutter. Having the proper structure from the start pays off.

Few examples:

- You can use the

Styleguide-Exampleproject as a starting point. - You can also use

cookiecutter-djangosince it has a ton of good stuff inside. - Or you can create something that works for your case & turn it into a cookiecutter project.

Models should take care of the data model and not much else.

It's a good idea to define a BaseModel, that you can inherit.

Usually, fields like created_at and updated_at are perfect candidates to go into a BaseModel.

Defining a primary key can also go there. Potential candidate for that is the UUIDField

Here's an example BaseModel:

from django.db import models

from django.utils import timezone

class BaseModel(models.Model):

created_at = models.DateTimeField(db_index=True, default=timezone.now)

updated_at = models.DateTimeField(auto_now=True)

class Meta:

abstract = TrueThen, whenever you need a new model, just inherit BaseModel:

class SomeModel(BaseModel):

passLets take a look at an example model:

class Course(BaseModel):

name = models.CharField(unique=True, max_length=255)

start_date = models.DateField()

end_date = models.DateField()

def clean(self):

if self.start_date >= self.end_date:

raise ValidationError("End date cannot be before start date")We are defining the model's clean method, because we want to make sure we get good data in our database.

Now, in order for the clean method to be called, someone must call full_clean on an instance of our model, before saving.

Our recommendation is to do that in the service, right before calling clean:

def course_create(*, name: str, start_date: date, end_date: date) -> Course:

obj = Course(name=name, start_date=start_date, end_date=end_date)

obj.full_clean()

obj.save()

return objThis also plays well with Django admin, because the forms used there will trigger full_clean on the instance.

We have few general rules of thumb for when to add validation in the model's clean method:

- If we are validating based on multiple, non-relational fields, of the model.

- If the validation itself is simple enough.

Validation should be moved to the service layer if:

- The validation logic is more complex.

- Spanning relations & fetching additional data is required.

It's OK to have validation both in

cleanand in the service, but we tend to move things in the service, if that's the case.

As proposed in this issue, if you can do validation using Django's constraints, then you should aim for that.

Less code to write, less to code to maintain, the database will take care of the data even if it's being inserted from a different place.

Lets look at an example!

class Course(BaseModel):

name = models.CharField(unique=True, max_length=255)

start_date = models.DateField()

end_date = models.DateField()

class Meta:

constraints = [

models.CheckConstraint(

name="start_date_before_end_date",

check=Q(start_date__lt=F("end_date"))

)

]Now, if we try to create new object via course.save() or via Course.objects.create(...), we are going to get an IntegrityError, rather than a ValidationError.

This can actually be a downside to the approach, because now, we have to deal with the IntegrityError, which does not always have the best error message.

The Django's documentation on constraints is quite lean, so you can check the following articles by Adam Johnson, for examples of how to use them:

- Using Django Check Constraints to Ensure Only One Field Is Set

- Django’s Field Choices Don’t Constrain Your Data

- Using Django Check Constraints to Prevent Self-Following

Model properties are great way to quickly access a derived value from a model's instance.

For example, lets look at the has_started and has_finished properties of our Course model:

from django.utils import timezone

from django.core.exceptions import ValidationError

class Course(BaseModel):

name = models.CharField(unique=True, max_length=255)

start_date = models.DateField()

end_date = models.DateField()

def clean(self):

if self.start_date >= self.end_date:

raise ValidationError("End date cannot be before start date")

@property

def has_started(self) -> bool:

now = timezone.now()

return self.start_date <= now.date()

@property

def has_finished(self) -> bool:

now = timezone.now()

return self.end_date <= now.date()Those properties are handy, because we can now refer to them in serializers or use them in templates.

We have few general rules of thumb, for when to add properties to the model:

- If we need a simple derived value, based on non-relational model fields, add a

@propertyfor that. - If the calculation of the derived value is simple enough.

Properties should be something else (service, selector, utility) in the following cases:

- If we need to span multiple relations or fetch additional data.

- If the calculation is more complex.

Keep in mind that those rules are vague, because context is quite often important. Use your best judgement!

Model methods are also very powerful tool, that can build on top of properties.

Lets see an example with the is_within(self, x) method:

from django.core.exceptions import ValidationError

from django.utils import timezone

class Course(BaseModel):

name = models.CharField(unique=True, max_length=255)

start_date = models.DateField()

end_date = models.DateField()

def clean(self):

if self.start_date >= self.end_date:

raise ValidationError("End date cannot be before start date")

@property

def has_started(self) -> bool:

now = timezone.now()

return self.start_date <= now.date()

@property

def has_finished(self) -> bool:

now = timezone.now()

return self.end_date <= now.date()

def is_within(self, x: date) -> bool:

return self.start_date <= x <= self.end_dateis_within cannot be a property, because it requires an argument. So it's a method instead.

Another great way for using methods in models is using them for attribute setting, when setting one attribute must always be followed by setting another attribute with a derived value.

An example:

from django.utils.crypto import get_random_string

from django.conf import settings

from django.utils import timezone

class Token(BaseModel):

secret = models.CharField(max_length=255, unique=True)

expiry = models.DateTimeField(blank=True, null=True)

def set_new_secret(self):

now = timezone.now()

self.secret = get_random_string(255)

self.expiry = now + settings.TOKEN_EXPIRY_TIMEDELTA

return selfNow, we can safely call set_new_secret, that'll produce correct values for both secret and expiry.

We have few general rules of thumb, for when to add methods to the model:

- If we need a simple derived value, that requires arguments, based on non-relational model fields, add a method for that.

- If the calculation of the derived value is simple enough.

- If setting one attribute always requires setting values to other attributes, use a method for that.

Models should be something else (service, selector, utility) in the following cases:

- If we need to span multiple relations or fetch additional data.

- If the calculation is more complex.

Keep in mind that those rules are vague, because context is quite often important. Use your best judgement!

Models need to be tested only if there's something additional to them - like validation, properties or methods.

Here's an example:

from datetime import timedelta

from django.test import TestCase

from django.core.exceptions import ValidationError

from django.utils import timezone

from project.some_app.models import Course

class CourseTests(TestCase):

def test_course_end_date_cannot_be_before_start_date(self):

start_date = timezone.now()

end_date = timezone.now() - timedelta(days=1)

course = Course(start_date=start_date, end_date=end_date)

with self.assertRaises(ValidationError):

course.full_clean()A few things to note here:

- We assert that a validation error is going to be raised if we call

full_clean. - We are not hitting the database at all, since there's no need for that. This can speed up certain tests.

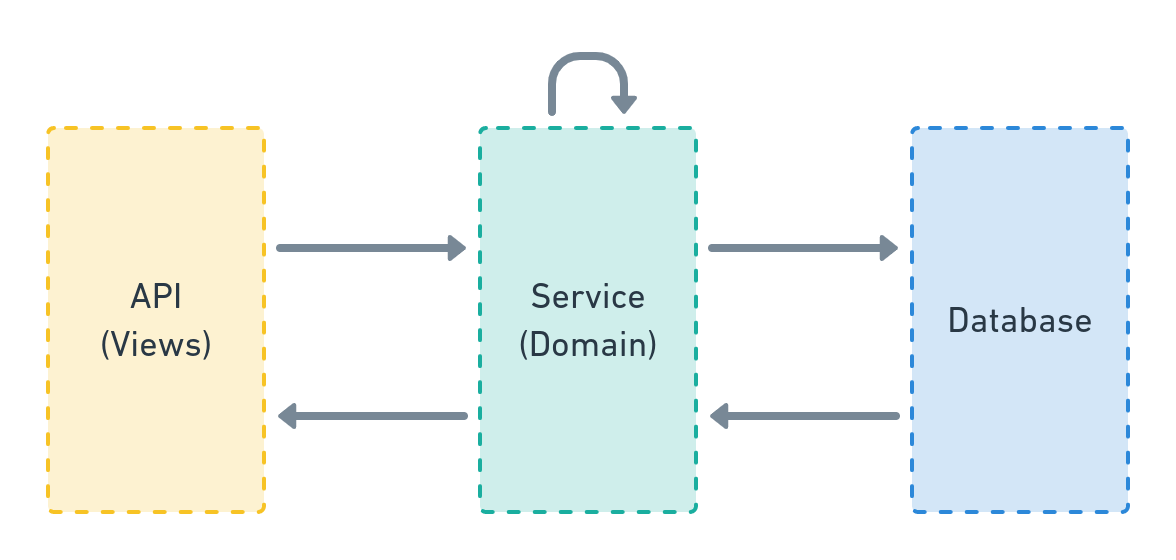

Services are where business logic lives.

The service layer speaks the specific domain language of the software, can access the database & other resources & can interact with other parts of your system.

Here's a very simple diagram, positioning the service layer in our Django apps:

A service can be:

- A simple function.

- A class.

- An entire module.

- Whatever makes sense in your case.

In most cases, a service can be simple function that:

- Lives in

<your_app>/services.pymodule. - Takes keyword-only arguments, unless it requires no or one argument.

- Is type-annotated (even if you are not using

mypyat the moment). - Interacts with the database, other resources & other parts of your system.

- Does business logic - from simple model creation to complex cross-cutting concerns, to calling external services & tasks.

An example service that creates a user:

def user_create(

*,

email: str,

name: str

) -> User:

user = User(email=email)

user.full_clean()

user.save()

profile_create(user=user, name=name)

confirmation_email_send(user=user)

return userAs you can see, this service calls 2 other services - profile_create and confirmation_email_send.

In this example, everything related to the user creation is in one place and can be traced.

Naming convention depends on your taste. It pays off to have something consistent throughout a project.

If we take the example above, our service is named user_create. The pattern is - <entity>_<action>.

This is what we prefer in HackSoft's projects. This seems odd at first, but it has few nice features:

- Namespacing. It's easy to spot all services starting with

user_and it's a good idea to put them in ausers.pymodule. - Greppability. Or in other words, if you want to see all actions for a specific entity, just grep for

user_.

If you have a simple-enough Django app with a bunch of services, they can all live happily in the service.py module.

But when things get big, you might want to split services.py into a folder with sub-modules, depending on the different sub-domains that you are dealing with in your app.

For example, lets say we have an authentication app, where we have 1 sub-module in our services module, that deals with jwt, and one sub-module that deals with oauth.

The structure may look like this:

services

├── __init__.py

├── jwt.py

└── oauth.py

There are lots of flavors here:

- You can do the import-export dance in

services/__init__.py, so you can import fromproject.authentication.serviceseverywhere else - You can create a folder-module,

jwt/__init__.py, and put the code there. - Basically, the structure is up to you. If you feel it's time to restructure and refactor - do so.

In most of our projects, we distinguish between "Pushing data to the database" and "Pulling data from the database":

- Services take care of the push.

- Selectors take care of the pull.

- Selectors can be viewed as a "sub-layer" to services, that's specialized in fetching data.

If this idea does not resonate well with you, you can just have services for both "kinds" of operations.

A selector follows the same rules as a service.

For example, in a module <your_app>/selectors.py, we can have the following:

def user_list(*, fetched_by: User) -> Iterable[User]:

user_ids = user_get_visible_for(user=fetched_by)

query = Q(id__in=user_ids)

return User.objects.filter(query)As you can see, user_get_visible_for is another selector.

You can return querysets, or lists or whatever makes sense to your specific case.

Since services hold our business logic, they are an ideal candidate for tests.

If you decide to cover the service layer with tests, we have few general rules of thumb to follow:

- The tests should cover the business logic in an exhaustive manner.

- The tests should hit the database - creating & reading from it.

- The tests should mock async task calls & everything that goes outside the project.

When creating the required state for a given test, one can use a combination of:

- Fakes (We recommend using

faker) - Other services, to create the required objects.

- Special test utility & helper methods.

- Factories (We recommend using

factory_boy) - Plain

Model.objects.create()calls, if factories are not yet introduced in the project. - Usually, whatever suits you better.

Let's take a look at our service from the example:

from django.contrib.auth.models import User

from django.core.exceptions import ValidationError

from project.payments.selectors import items_get_for_user

from project.payments.models import Item, Payment

from project.payments.tasks import payment_charge

def item_buy(

*,

item: Item,

user: User,

) -> Payment:

if item in items_get_for_user(user=user):

raise ValidationError(f'Item {item} already in {user} items.')

payment = Payment.objects.create(

item=item,

user=user,

successful=False

)

payment_charge.delay(payment_id=payment.id)

return paymentThe service:

- Calls a selector for validation.

- Creates an object.

- Delays a task.

Those are our tests:

from unittest.mock import patch

from django.test import TestCase

from django.contrib.auth.models import User

from django.core.exceptions import ValidationError

from django_styleguide.payments.services import item_buy

from django_styleguide.payments.models import Payment, Item

class ItemBuyTests(TestCase):

def setUp(self):

self.user = User.objects.create_user(username='Test User')

self.item = Item.objects.create(

name='Test Item',

description='Test Item description',

price=10.15

)

@patch('project.payments.services.items_get_for_user')

def test_buying_item_that_is_already_bought_fails(self, items_get_for_user_mock):

"""

Since we already have tests for `items_get_for_user`,

we can safely mock it here and give it a proper return value.

"""

items_get_for_user_mock.return_value = [self.item]

with self.assertRaises(ValidationError):

item_buy(user=self.user, item=self.item)

@patch('project.payments.services.payment_charge.delay')

def test_buying_item_creates_a_payment_and_calls_charge_task(

self,

payment_charge_mock

):

self.assertEqual(0, Payment.objects.count())

payment = item_buy(user=self.user, item=self.item)

self.assertEqual(1, Payment.objects.count())

self.assertEqual(payment, Payment.objects.first())

self.assertFalse(payment.successful)

payment_charge_mock.assert_called()When using services & selectors, all of your APIs should look simple & identical.

When we are creating new APIs, we follow those general rules:

- Have 1 API per operation. This means, for CRUD on a model, having 4 APIs.

- Inherit from the most simple

APIVieworGenericAPIView.- Avoid the more abstract classes, since they tend to manage things via serializers & we want to do that via services & selectors.

- Don't do business logic in your API.

- You can do object fetching / data manipulation in your APIs (potentially, you can extract that to somewhere else).

- If you are calling

some_servicein your API, you can extract object fetching / data manipulation tosome_service_parse.

- If you are calling

- Basically, keep the APIs are simple as possible. They are an interface towards your core business logic.

When we are talking about APIs, we need a way to deal with data serialization - both incoming & outgoing data.

Here are our rules for API serialization:

- There should be a dedicated input serializer & a dedicated output serializer.

- Input serializer takes care of the data coming in.

- Output serializer takes care of the data coming out.

- In terms of serialization, Use whatever abstraction works for you.

In case you are using DRF's serializers, here are our rules:

- Serializer should be nested in the API and be named either

InputSerializerorOutputSerializer. - Our preference is for both serializers to inherit from the simpler

Serializerand avoid usingModelSerializer- This is a matter of preference and choice. If

ModelSerializeris working fine for you, use it.

- This is a matter of preference and choice. If

- If you need a nested serializer, use the

inline_serializerutil. - Reuse serializers as little as possible.

- Reusing serializers may expose you to unexpected behavior, when something changes in the base serializers.

For our APIs we use the following naming convention: <Entity><Action>Api.

Here are few examples: UserCreateApi, UserSendResetPasswordApi, UserDeactivateApi, etc.

A dead-simple list API should look like that:

from rest_framework.views import APIView

from rest_framework import serializers

from rest_framework.response import Response

from styleguide_example.users.selectors import user_list

from styleguide_example.users.models import BaseUser

class UserListApi(APIView):

class OutputSerializer(serializers.Serializer):

id = serializers.CharField()

email = serializers.CharField()

def get(self, request):

users = user_list()

data = self.OutputSerializer(users, many=True).data

return Response(data)Keep in mind this API is public by default. Authentication is up to you.

At first glance, this is tricky, since our APIs are inheriting the plain APIView from DRF, while filtering and pagination are baked into the generic ones:

That's why, we take the following approach:

- Selectors take care of the actual filtering.

- APIs take care of filter parameter serialization.

- If you need some of the generic paginations, provided by DRF, the API should take care of that.

- If you need a different pagination, or you are implementing it yourself, either add a new layer to handle pagination or let the selector do that for you.

Let's look at the example, where we rely on pagination, provided by DRF:

from rest_framework.views import APIView

from rest_framework import serializers

from styleguide_example.api.mixins import ApiErrorsMixin

from styleguide_example.api.pagination import get_paginated_response, LimitOffsetPagination

from styleguide_example.users.selectors import user_list

from styleguide_example.users.models import BaseUser

class UserListApi(ApiErrorsMixin, APIView):

class Pagination(LimitOffsetPagination):

default_limit = 1

class FilterSerializer(serializers.Serializer):

id = serializers.IntegerField(required=False)

# Important: If we use BooleanField, it will default to False

is_admin = serializers.NullBooleanField(required=False)

email = serializers.EmailField(required=False)

class OutputSerializer(serializers.Serializer):

id = serializers.CharField()

email = serializers.CharField()

is_admin = serializers.BooleanField()

def get(self, request):

# Make sure the filters are valid, if passed

filters_serializer = self.FilterSerializer(data=request.query_params)

filters_serializer.is_valid(raise_exception=True)

users = user_list(filters=filters_serializer.validated_data)

return get_paginated_response(

pagination_class=self.Pagination,

serializer_class=self.OutputSerializer,

queryset=users,

request=request,

view=self

)When we look at the API, we can identify few things:

- There's a

FilterSerializer, which will take care of the query parameters. If we don't do this here, we'll have to do it elsewhere & DRF serializers are great at this job. - We pass the filters to the

user_listselector - We use the

get_paginated_responseutility, to return a .. paginated response.

Now, let's look at the selector:

import django_filters

from styleguide_example.users.models import BaseUser

class BaseUserFilter(django_filters.FilterSet):

class Meta:

model = BaseUser

fields = ('id', 'email', 'is_admin')

def user_list(*, filters=None):

filters = filters or {}

qs = BaseUser.objects.all()

return BaseUserFilter(filters, qs).qsAs you can see, we are leveraging the powerful django-filter library.

👀 The key thing here is that the selector is responsible for the filtering. You can always use something else, as a filtering abstaction. For most of the cases,

django-filteris more than enough.

Finally, let's look at get_paginated_response:

from rest_framework.response import Response

def get_paginated_response(*, pagination_class, serializer_class, queryset, request, view):

paginator = pagination_class()

page = paginator.paginate_queryset(queryset, request, view=view)

if page is not None:

serializer = serializer_class(page, many=True)

return paginator.get_paginated_response(serializer.data)

serializer = serializer_class(queryset, many=True)

return Response(data=serializer.data)This is basically a code, extracted from within DRF.

Same goes for the LimitOffsetPagination:

from collections import OrderedDict

from rest_framework.pagination import LimitOffsetPagination as _LimitOffsetPagination

from rest_framework.response import Response

class LimitOffsetPagination(_LimitOffsetPagination):

default_limit = 10

max_limit = 50

def get_paginated_data(self, data):

return OrderedDict([

('limit', self.limit),

('offset', self.offset),

('count', self.count),

('next', self.get_next_link()),

('previous', self.get_previous_link()),

('results', data)

])

def get_paginated_response(self, data):

"""

We redefine this method in order to return `limit` and `offset`.

This is used by the frontend to construct the pagination itself.

"""

return Response(OrderedDict([

('limit', self.limit),

('offset', self.offset),

('count', self.count),

('next', self.get_next_link()),

('previous', self.get_previous_link()),

('results', data)

]))What we basically did is reverse-engineered the generic APIs.

👀 Again, if you need something else for pagination, you can always implement it & use it in the same manner. There are cases, where the selector needs to take care of the pagination. We approach those cases the same way we approach filtering.

You can find the code for the example list API with filters & pagination in the Styleguide Example project.

Here's an example:

class CourseDetailApi(SomeAuthenticationMixin, APIView):

class OutputSerializer(serializers.Serializer):

id = serializers.CharField()

name = serializers.CharField()

start_date = serializers.DateField()

end_date = serializers.DateField()

def get(self, request, course_id):

course = course_get(id=course_id)

serializer = self.OutputSerializer(course)

return Response(serializer.data)Here's an example:

class CourseCreateApi(SomeAuthenticationMixin, APIView):

class InputSerializer(serializers.Serializer):

name = serializers.CharField()

start_date = serializers.DateField()

end_date = serializers.DateField()

def post(self, request):

serializer = self.InputSerializer(data=request.data)

serializer.is_valid(raise_exception=True)

course_create(**serializer.validated_data)

return Response(status=status.HTTP_201_CREATED)Here's an example:

class CourseUpdateApi(SomeAuthenticationMixin, APIView):

class InputSerializer(serializers.Serializer):

name = serializers.CharField(required=False)

start_date = serializers.DateField(required=False)

end_date = serializers.DateField(required=False)

def post(self, request, course_id):

serializer = self.InputSerializer(data=request.data)

serializer.is_valid(raise_exception=True)

course_update(course_id=course_id, **serializer.validated_data)

return Response(status=status.HTTP_200_OK)When our APIs receive an object_id, the question that arises is: Where should we fetch that object?

We have several options:

- We can pass that object to a serializer, which has a

PrimaryKeyRelatedField(or aSlugRelatedFieldfor that matter) - We can do some kind of object fetching in the API & pass the object to a service or a selector.

- We can pass the id to the service / selector and do the object fetching there.

What approach we take is a matter of project context & preference.

What we usually do is to fetch objects on the API level, using a special get_object util:

def get_object(model_or_queryset, **kwargs):

"""

Reuse get_object_or_404 since the implementation supports both Model && queryset.

Catch Http404 & return None

"""

try:

return get_object_or_404(model_or_queryset, **kwargs)

except Http404:

return NoneThis is a very basic utility, that handles the exception and returns None instead.

Whatever you do, make sure to keep it consistent.

In case you need to use a nested serializer, you can do the following thing:

class Serializer(serializers.Serializer):

weeks = inline_serializer(many=True, fields={

'id': serializers.IntegerField(),

'number': serializers.IntegerField(),

})The implementation of inline_serializer can be found here, in the Styleguide-Example repo.

Sometimes, the end result of an API can be quite complex. Sometimes, we want to optimize the queries that we do and the optimization itself can be quite complex.

Trying to stick with just an OutputSerializer in that case might limit our options.

In those cases, we can implement our output serialization as a function, and have the optimizations we need there, instead of having all the optimizations in the selector.

Lets take this API as an example:

class SomeGenericFeedApi(BaseApi):

def get(self, request):

feed = some_feed_get(

user=request.user,

)

data = some_feed_serialize(feed)

return Response(data)In this scenario, some_feed_get has the responsibility of returning a list of feed items (can be ORM objects, can be just IDs, can be whatever works for you).

And we want to push the complexity of serializing this feed, in an optimal manner, to the serializer function - some_feed_serialize.

This means we don't have to do any unnecessary prefetches & optimizations in some_feed_get.

Here's an example of some_feed_serialize:

class FeedItemSerializer(serializers.Serializer):

... some fields here ...

calculated_field = serializers.IntegerField(source="_calculated_field")

def some_feed_serialize(feed: List[FeedItem]):

feed_ids = [feed_item.id for feed_item in feed]

# Refetch items with more optimizations

# Based on the relations that are going in

objects = FeedItem.objects.select_related(

# ... as complex as you want ...

).prefetch_related(

# ... as complex as you want ...

).filter(

id__in=feed_ids

).order_by(

"-some_timestamp"

)

some_cache = get_some_cache(feed_ids)

result = []

for feed_item in objects:

# An example, adding additional fields for the serializer

# That are based on values outside of our current object

# This may be some optimization to save queries

feed_item._calculated_field = some_cache.get(feed_item.id)

result.append(FeedItemSerializer(feed_item).data)

return resultAs you can see, this is a pretty generic example, but the idea is simple:

- Refetch your data, with the needed joins & prefetches.

- Fetch or build in-memory caches, that will save you queries for specific computed values.

- Return a result, that's ready to be an API response.

Even though this is labeled as "advanced serialization", the pattern is really powerful and can be used for all serializations.

Such serializer functions usually live in a serializers.py module, in the corresponding Django app.

We usually organize our urls the same way we organize our APIs - 1 url per API, meaning 1 url per action.

A general rule of thumb is to split urls from different domains in their own domain_patterns list & include from urlpatterns.

Here's an example with the APIs from above:

from django.urls import path, include

from project.education.apis import (

CourseCreateApi,

CourseUpdateApi,

CourseListApi,

CourseDetailApi,

CourseSpecificActionApi,

)

course_patterns = [

path('', CourseListApi.as_view(), name='list'),

path('<int:course_id>/', CourseDetailApi.as_view(), name='detail'),

path('create/', CourseCreateApi.as_view(), name='create'),

path('<int:course_id>/update/', CourseUpdateApi.as_view(), name='update'),

path(

'<int:course_id>/specific-action/',

CourseSpecificActionApi.as_view(),

name='specific-action'

),

]

urlpatterns = [

path('courses/', include((course_patterns, 'courses'))),

]Splitting urls like that can give you the extra flexibility to move separate domain patterns to separate modules, especially for really big projects, where you'll often have merge conflicts in urls.py.

When it comes to Django settings, we tend to follow the folder structure from cookiecutter-django, with few adjustments:

- We separate Django specific settings from other settings.

- Everything should be included in

base.py.- There should be nothing that's only included in

production.py. - Things that need to only work in production are controlled via environment variables.

- There should be nothing that's only included in

Here's the folder structure of our Styleguide-Example project:

config

├── __init__.py

├── django

│ ├── __init__.py

│ ├── base.py

│ ├── local.py

│ ├── production.py

│ └── test.py

├── settings

│ ├── __init__.py

│ ├── celery.py

│ ├── cors.py

│ ├── sentry.py

│ └── sessions.py

├── urls.py

├── env.py

└── wsgi.py

├── asgi.py

In config/django, we put everything that's Django related:

base.pycontains most of the settings & imports everything else fromconfig/settingsproduction.pyimports frombase.pyand then overwrites some specific settings for production.test.pyimports frombase.pyand then overwrites some specific settings for running tests.- This should be used as the settings module in

pytest.ini.

- This should be used as the settings module in

local.pyimports frombase.pyand can overwrite some specific settings for local development.- If you want to use that, point to

localinmanage.py. Otherwise stick withbase.py

- If you want to use that, point to

In config/settings, we put everything else:

- Celery configuration.

- 3rd party configurations.

- etc.

This gives you a nice separation of modules.

Additionally, we usually have config/env.py with the following code:

import environ

env = environ.Env()And then, whenever we need to read something from the environment, we import like that:

from config.env import envUsually, at the end of the base.py module, we import everything from config/settings:

from config.settings.cors import * # noqa

from config.settings.sessions import * # noqa

from config.settings.celery import * # noqa

from config.settings.sentry import * # noqaIn a lot of examples, you'll see that environment variables are usually prefixed with DJANGO_. This is very helpful when there are other applications running alongside your Django app & reading from the same environment.

We tend to prefix with DJANGO_ only DJANGO_SETTINGS_MODULE and DJANGO_DEBUG & not prefix anything else.

This is mostly up to personal preference. Just make sure you are consistent with that.

Since everything should be imported in base.py, but sometimes we don't want to configure a certain integration for local development, we derived the following approach:

- Integration-specific settings are placed in

config/settings/some_integration.py - There's always a boolean setting called

USE_SOME_INTEGRATION, which reads from the environment & defaults toFalse. - If the value is

True, then proceed reading other settings & failing if things are not present in the environment.

For example, lets take a look at config/settings/sentry.py:

from config.env import env

SENTRY_DSN = env('SENTRY_DSN', default='')

if SENTRY_DSN:

import sentry_sdk

from sentry_sdk.integrations.django import DjangoIntegration

from sentry_sdk.integrations.celery import CeleryIntegration

# ... we proceed with sentry settings here ...

# View the full file here - https://github.com/HackSoftware/Styleguide-Example/blob/master/config/settings/sentry.pyHaving a local .env is a nice way of providing values for your settings.

And the good thing is, django-environ provides you with a way to do that:

# That's in the beginning of base.py

import os

from config.env import env, environ

# Build paths inside the project like this: os.path.join(BASE_DIR, ...)

BASE_DIR = environ.Path(__file__) - 3

env.read_env(os.path.join(BASE_DIR, ".env"))Now you can have a .env (but it's not required) file in your project root & place values for your settings there.

There are 2 things worth mentioning here:

- Don't put

.envin your source control, since this will leak credentials. - Rather put an

.env.examplewith empty values for everything, so new developers can figure out what's being used.

👀 If you want the code, hop to the

Styleguide-Exampleproject - https://github.com/HackSoftware/Styleguide-Example/blob/master/styleguide_example/api/exception_handlers.py

Errors & exception handling is a big topic & quite often - the details are specific for a given project.

That's why we'll split things into two - general guidelines, followed by some specific approaches for error handling.

Our general guidelines are:

- Know how exception handling works (we'll give context for Django Rest Framework).

- Describe how your API errors are going to look like.

- Know how to change the default exception handling behavior.

Followed by some specific approaches:

- Use DRF's default exceptions, with very little modifications.

- HackSoft's proposed approach.

DRF has an excellent guide on how exceptions are being handled, so make sure to read it first - https://www.django-rest-framework.org/api-guide/exceptions/

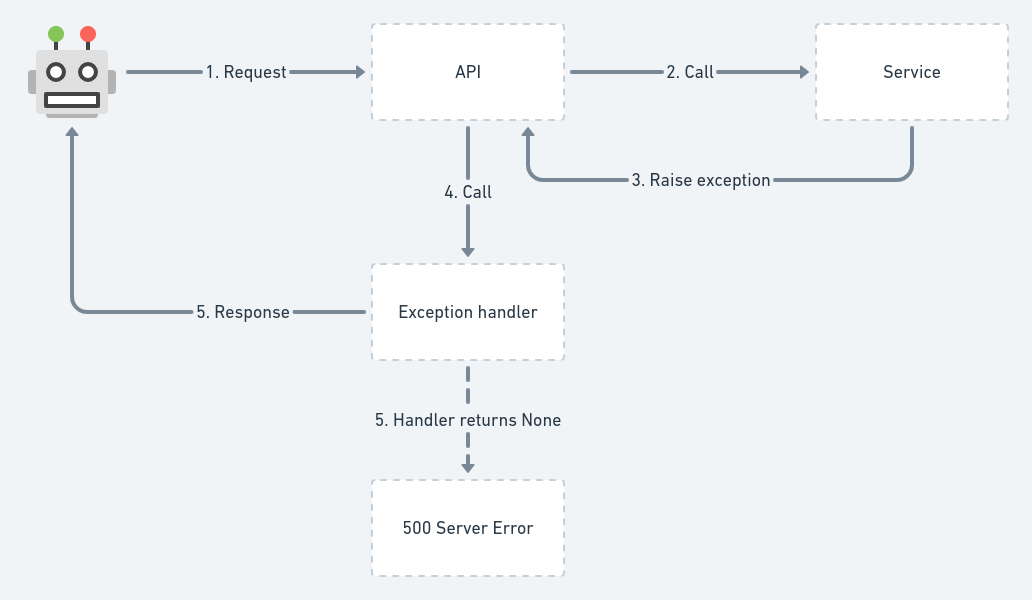

Additonally, here's a neat diadgram with an overview of the process:

Basically, if the exception handler cannot handle the given exception & returns None, this will result in an unhandled exception & a 500 Server Error. This is often good, because you won't be silencing errors, that you need to pay attention to.

Now, there are some quirks, that we need to pay attention to.

For example, if we simply raise a rest_framework.exceptions.ValidationError like that:

from rest_framework import exceptions

def some_service():

raise ValidationError("Error message here.")The response payload is going to look like this:

[

"Some message"

]This looks strange, because if we do it like this:

from rest_framework import exceptions

def some_service():

raise exceptions.ValidationError({"error": "Some message"})The response payload is going to look like this:

{

"error": "Some message"

}That's basically what we passed as the detail of the ValidationError. But it's a different data structure from the initial array.

Now, if we decide to raise another of the DRF's built-in exceptions:

from rest_framework import exceptions

def some_service():

raise exceptions.NotFound()The response payload is going to look like this:

{

"detail": "Not found."

}That's entirely different from what we saw as behavior from the ValidationError and this might cause problems.

So far, the default DRF behavior can get us:

- An array.

- A dictionarry.

- A specific

{"detail": "something"}result.

So if we need to use the default DRF behavior, we need to take care of this inconsistency.

Now, DRF's default exception handling is not playing nice with Django's ValidationError.

This piece of code:

from django.core.exceptions import ValidationError as DjangoValidationError

def some_service():

raise DjangoValidationError("Some error message")Will result in an unhandled exception, causing 500 Server Error.

This will also happen if this ValidationError comes from model validation, for example:

def some_service():

user = BaseUser()

user.full_clean() # Throws ValidationError

user.save()This will also result in 500 Server Error.

If we want to start handling this, as if it was rest_framework.exceptions.ValidationError, we need to roll-out our own custom exception handler:

from django.core.exceptions import ValidationError as DjangoValidationError

from rest_framework.views import exception_handler

from rest_framework.serializers import as_serializer_error

from rest_framework import exceptions

def custom_exception_handler(exc, ctx):

if isinstance(exc, DjangoValidationError):

exc = exceptions.ValidationError(as_serializer_error(exc))

response = exception_handler(exc, ctx)

# If unexpected error occurs (server error, etc.)

if response is None:

return response

return responseThis is basically the default implementation, with the addition of this piece of code:

if isinstance(exc, DjangoValidationError):

exc = exceptions.ValidationError(as_serializer_error(exc))Since we need to map between django.core.exceptions.ValidationError and rest_framework.exceptions.ValidationError, we are using DRF's as_serializer_error, which is used internally in the serializers, just for that.

With that, we can now have Django's ValidationError playing nice with DRF's exception handler.

This is very important and should be done as early as possible in any given project.

This is basically agreening upon what the interface of your API errors - How an error is going to look like as an API response?

This is very project specific, you can use some of the popular APIs for inspiration:

- Stripe - https://stripe.com/docs/api/errors

As an example, we might decide that our errors are going to look like this:

4**and5**status codes for different types of errors.- Each error will be a dictionarry with a single

messagekey, containing the error message.

{

"message": "Some error message here"

}That's simple enough:

400will be used for validation errors.401for auth errors.403for permission errors.404for not found errors.429for throttling errors.500for server errors (we need to be careful not to silence an exception causing 500 and always report that in services like Sentry)

Again, this is up to you & it's specific to the project. We'll propose something similiar for one of the specific approaches.

This is also important, because when you decide how your errors are going to look like, you need to implement this as custom exception handling.

We've already provided an example for that in the paragraph above, talking about Django's ValidationError.

We'll also provide additional examples in the sections below.

DRF's error handling is good. It'd be great, if the end result was always consistent. Those are the little modifications that we are going to do.

We want to end up with errors, always looking like that:

{

"detail": "Some error"

}or

{

"detail": ["Some error", "Another error"]

}or

{

"detail": { "key": "... some arbitrary nested structure ..." }

}Basically, make sure we always have a dictionary with a detail key.

Additonally, we want to handle Django's ValidationError as well.

In order to achieve that, this is how our custom exception handler is going to look like:

from django.core.exceptions import ValidationError as DjangoValidationError, PermissionDenied

from django.http import Http404

from rest_framework.views import exception_handler

from rest_framework import exceptions

from rest_framework.serializers import as_serializer_error

def drf_default_with_modifications_exception_handler(exc, ctx):

if isinstance(exc, DjangoValidationError):

exc = exceptions.ValidationError(as_serializer_error(exc))

if isinstance(exc, Http404):

exc = exceptions.NotFound()

if isinstance(exc, PermissionDenied):

exc = exceptions.PermissionDenied()

response = exception_handler(exc, ctx)

# If unexpected error occurs (server error, etc.)

if response is None:

return response

if isinstance(exc.detail, (list, dict)):

response.data = {

"detail": response.data

}

return responseWe kind-of replicate the original exception handler, so we can deal with an APIException after that (looking for detail).

Now, lets run a set of tests:

Code:

def some_service():

raise DjangoValidationError("Some error message")Response:

{

"detail": {

"non_field_errors": [

"Some error message"

]

}

}Code:

from django.core.exceptions import PermissionDenied

def some_service():

raise PermissionDenied()Response:

{

"detail": "You do not have permission to perform this action."

}Code:

from django.http import Http404

def some_service():

raise Http404()Response:

{

"detail": "Not found."

}Code:

def some_service():

raise RestValidationError("Some error message")Response:

{

"detail": [

"Some error message"

]

}Code:

def some_service():

raise RestValidationError(detail={"error": "Some error message"})Response:

{

"detail": {

"error": "Some error message"

}

}Code:

class NestedSerializer(serializers.Serializer):

bar = serializers.CharField()

class PlainSerializer(serializers.Serializer):

foo = serializers.CharField()

email = serializers.EmailField(min_length=200)

nested = NestedSerializer()

def some_service():

serializer = PlainSerializer(data={

"email": "foo",

"nested": {}

})

serializer.is_valid(raise_exception=True)Response:

{

"detail": {

"foo": [

"This field is required."

],

"email": [

"Ensure this field has at least 200 characters.",

"Enter a valid email address."

],

"nested": {

"bar": [

"This field is required."

]

}

}

}Code:

from rest_framework import exceptions

def some_service():

raise exceptions.Throttled()Response:

{

"detail": "Request was throttled."

}Code:

def some_service():

user = BaseUser()

user.full_clean()Response:

{

"detail": {

"password": [

"This field cannot be blank."

],

"email": [

"This field cannot be blank."

]

}

}We are going to propose an approach, that can be easily extended into something that works well for you.

Here are the key ideas:

- Your application will have its own hierarchy of exceptions, that are going to be thrown by the business logic.

- Lets say, for simplicity, that we are going to have only 1 error -

ApplicationError.- This is going to be defined in a special

coreapp, withinexceptionsmodule. Basically, havingproject.core.exceptions.ApplicationError.

- This is going to be defined in a special

- We want to let DRF handle everything else, by default.

ValidationErroris now special and it's going to be handled differently.ValidationErrorshould only come from either serializer or a model validation.

We are going to define the following structure for our errors:

{

"message": "The error message here",

"extra": {}

}The extra key can hold arbitrary data, for the purposes of passing information to the frontend.

For example, whenerver we have a ValidationError (usually coming from a Serializer or a Model), we are going to present the error like that:

{

"message": "Validation error.",

"extra": {

"fields": {

"password": [

"This field cannot be blank."

],

"email": [

"This field cannot be blank."

]

}

},

}This can be communicated with the frontend, so they can look for extra.fields, to present those specific errors to the user.

In order to achieve that, the custom exception handler is going to look like this:

from django.core.exceptions import ValidationError as DjangoValidationError, PermissionDenied

from django.http import Http404

from rest_framework.views import exception_handler

from rest_framework import exceptions

from rest_framework.serializers import as_serializer_error

from rest_framework.response import Response

from styleguide_example.core.exceptions import ApplicationError

def hacksoft_proposed_exception_handler(exc, ctx):

"""

{

"message": "Error message",

"extra": {}

}

"""

if isinstance(exc, DjangoValidationError):

exc = exceptions.ValidationError(as_serializer_error(exc))

if isinstance(exc, Http404):

exc = exceptions.NotFound()

if isinstance(exc, PermissionDenied):

exc = exceptions.PermissionDenied()

response = exception_handler(exc, ctx)

# If unexpected error occurs (server error, etc.)

if response is None:

if isinstance(exc, ApplicationError):

data = {

"message": exc.message,

"extra": exc.extra

}

return Response(data, status=400)

return response

if isinstance(exc.detail, (list, dict)):

response.data = {

"detail": response.data

}

if isinstance(exc, exceptions.ValidationError):

response.data["message"] = "Validation error"

response.data["extra"] = {

"fields": response.data["detail"]

}

else:

response.data["message"] = response.data["detail"]

response.data["extra"] = {}

del response.data["detail"]

return responseTake a look at that code & try to understand what's going on. The strategy is - reuse as much as possible from DRF & then adjust.

Now, we are going to have the following behavior:

Code:

from styleguide_example.core.exceptions import ApplicationError

def trigger_application_error():

raise ApplicationError(message="Something is not correct", extra={"type": "RANDOM"})Response:

{

"message": "Something is not correct",

"extra": {

"type": "RANDOM"

}

}Code:

def some_service():

raise DjangoValidationError("Some error message")Response:

{

"message": "Validation error",

"extra": {

"fields": {

"non_field_errors": [

"Some error message"

]

}

}

}Code:

from django.core.exceptions import PermissionDenied

def some_service():

raise PermissionDenied()Response:

{

"message": "You do not have permission to perform this action.",

"extra": {}

}Code:

from django.http import Http404

def some_service():

raise Http404()Response:

{

"message": "Not found.",

"extra": {}

}Code:

def some_service():

raise RestValidationError("Some error message")Response:

{

"message": "Validation error",

"extra": {

"fields": [

"Some error message"

]

}

}Code:

def some_service():

raise RestValidationError(detail={"error": "Some error message"})Response:

{

"message": "Validation error",

"extra": {

"fields": {

"error": "Some error message"

}

}

}Code:

class NestedSerializer(serializers.Serializer):

bar = serializers.CharField()

class PlainSerializer(serializers.Serializer):

foo = serializers.CharField()

email = serializers.EmailField(min_length=200)

nested = NestedSerializer()

def some_service():

serializer = PlainSerializer(data={

"email": "foo",

"nested": {}

})

serializer.is_valid(raise_exception=True)Response:

{

"message": "Validation error",

"extra": {

"fields": {

"foo": [

"This field is required."

],

"email": [

"Ensure this field has at least 200 characters.",

"Enter a valid email address."

],

"nested": {

"bar": [

"This field is required."

]

}

}

}

}Code:

from rest_framework import exceptions

def some_service():

raise exceptions.Throttled()Response:

{

"message": "Request was throttled.",

"extra": {}

}Code:

def some_service():

user = BaseUser()

user.full_clean()Response:

{

"message": "Validation error",

"extra": {

"fields": {

"password": [

"This field cannot be blank."

],

"email": [

"This field cannot be blank."

]

}

}

}Now, this can be extended & made to better suit your needs:

- You can have

ApplicationValidationErrorandApplicationPermissionError, as an additional hierarchy. - You can reimplement DRF's default exception handler, instead of reusing it (copy-paste it & adjust to your needs).

The general idea is - figure out what kind of error handling you need and then implement it accordingly.

As you can see, we can mold exception handling to our needs.

You can start handling more stuff - for example - translating django.core.exceptions.ObjectDoesNotExist to rest_framework.exceptions.NotFound.

You can even handle all exceptions, but then, you should be sure those exceptions are being logged properly, otherwise you might silence something that's important.

In our Django projects, we split our tests depending on the type of code they represent.

Meaning, we generally have tests for models, services, selectors & APIs / views.

The file structure usually looks like this:

project_name

├── app_name

│ ├── __init__.py

│ └── tests

│ ├── __init__.py

│ ├── models

│ │ └── __init__.py

│ │ └── test_some_model_name.py

│ ├── selectors

│ │ └── __init__.py

│ │ └── test_some_selector_name.py

│ └── services

│ ├── __init__.py

│ └── test_some_service_name.py

└── __init__.py

We follow 2 general naming conventions:

- The test file names should be

test_the_name_of_the_thing_that_is_tested.py - The test case should be

class TheNameOfTheThingThatIsTestedTests(TestCase):

For example, if we have:

def a_very_neat_service(*args, **kwargs):

passWe are going to have the following for file name:

project_name/app_name/tests/services/test_a_very_neat_service.py

And the following for test case:

class AVeryNeatServiceTests(TestCase):

passFor tests of utility functions, we follow a similar pattern.

For example, if we have project_name/common/utils.py, then we are going to have project_name/common/tests/test_utils.py and place different test cases in that file.

If we are to split the utils.py module into submodules, the same will happen for the tests:

project_name/common/utils/files.pyproject_name/common/tests/utils/test_files.py

We try to match the structure of our modules with the structure of their respective tests.

We use Celery for the following general cases:

- Communicating with 3rd party services (sending emails, notifications, etc.)

- Offloading heavier computational tasks outside the HTTP cycle.

- Periodic tasks (using Celery beat)

We try to treat Celery as if it's just another interface to our core logic - meaning - don't put business logic there.

An example task might look like this:

from celery import shared_task

from project.app.services import some_service_name as service

@shared_task

def some_service_name(*args, **kwargs):

service(*args, **kwargs)This is a task, having the same name as a service, which holds the actual business logic.

Of course, we can have more complex situations, like a chain or chord of tasks, each of them doing different domain related logic. In that case, it's hard to isolate everything in a service, because we now have dependencies between the tasks.

If that happens, we try to expose an interface to our domain & let the tasks work with that interface.

One can argue that having an ORM object is an interface by itself, and that's true. Sometimes, you can just update your object from a task & that's OK.

But there are times where you need to be strict and don't let tasks do database calls straight from the ORM, but rather, via an exposed interface for that.

More complex scenarios depend on their context. Make sure you are aware of the architecture & the decisions you are making.

We put Celery configuration in a Django app called tasks. The Celery config itself is located in apps.py, in TasksConfig.ready method.

This Django app also holds any additional utilities, related to Celery.

Here's an example project/tasks/apps.py file:

import os

from celery import Celery

from django.apps import apps, AppConfig

from django.conf import settings

os.environ.setdefault('DJANGO_SETTINGS_MODULE', 'config.settings.local')

app = Celery('project')

class TasksConfig(AppConfig):

name = 'project.tasks'

verbose_name = 'Celery Config'

def ready(self):

app.config_from_object('django.conf:settings', namespace="CELERY")

app.autodiscover_tasks()

@app.task(bind=True)

def debug_task(self):

from celery.utils.log import base_logger

base_logger = base_logger

base_logger.debug('debug message')

base_logger.info('info message')

base_logger.warning('warning message')

base_logger.error('error message')

base_logger.critical('critical message')

print('Request: {0!r}'.format(self.request))

return 42Tasks are located in tasks.py modules in different apps.

We follow the same rules as with everything else (APIs, services, selectors): if the tasks for a given app grow too big, split them by domain.

Meaning, you can end up with tasks/domain_a.py and tasks/domain_b.py. All you need to do is import them in tasks/__init__.py for Celery to autodiscover them.

The general rule of thumb is - split your tasks in a way that'll make sense to you.

In some cases, you need to invoke a task from a service or vice-versa:

# project/app/services.py

from project.app.tasks import task_function_1

def service_function_1():

print('I delay a task!')

task_function_1.delay()

def service_function_2():

print('I do not delay a task!')# project/app/tasks.py

from celery import shared_task

from project.app.services import service_function_2

@shared_task

def task_function_1():

print('I do not call a service!')

@shared_task

def task_function_2():

print('I call a service!')

service_function_2()Unfortunately, this will result in a circular import.

What we usually do is we import the service function inside the task function:

# project/app/tasks.py

from celery import shared_task

@shared_task

def task_function_1():

print('I do not call a service!')

@shared_task

def task_function_2():

from project.app.services import service_function_2 # <--

print('I call a service!')

service_function_2()- Note: Depending on the case, you may want to import the task function inside the service function. This is OK and will still prevent the circular import between service & task functions.

Managing periodic tasks is quite important, especially when you have tens or hundreds of them.

We use Celery Beat + django_celery_beat.schedulers:DatabaseScheduler + django-celery-beat for our periodic tasks.

The extra thing that we do is to have a management command, called setup_periodic_tasks, which holds the definition of all periodic tasks within the system. This command is located in the tasks app, discussed above.

Here's how project.tasks.management.commands.setup_periodic_tasks.py looks like:

from django.core.management.base import BaseCommand

from django.db import transaction

from django_celery_beat.models import IntervalSchedule, CrontabSchedule, PeriodicTask

from project.app.tasks import some_periodic_task

class Command(BaseCommand):

help = f"""

Setup celery beat periodic tasks.

Following tasks will be created:

- {some_periodic_task.name}

"""

@transaction.atomic

def handle(self, *args, **kwargs):

print('Deleting all periodic tasks and schedules...\n')

IntervalSchedule.objects.all().delete()

CrontabSchedule.objects.all().delete()

PeriodicTask.objects.all().delete()

periodic_tasks_data = [

{

'task': some_periodic_task

'name': 'Do some peridoic stuff',

# https://crontab.guru/#15_*_*_*_*

'cron': {

'minute': '15',

'hour': '*',

'day_of_week': '*',

'day_of_month': '*',

'month_of_year': '*',

},

'enabled': True

},

]

for periodic_task in periodic_tasks_data:

print(f'Setting up {periodic_task["task"].name}')

cron = CrontabSchedule.objects.create(

**periodic_task['cron']

)

PeriodicTask.objects.create(

name=periodic_task['name'],

task=periodic_task['task'].name,

crontab=cron,

enabled=periodic_task['enabled']

)Few key things:

- We use this task as part of a deploy procedure.

- We always put a link to

crontab.guruto explain the cron. Otherwise it's unreadable. - Everything is in one place.

⚠️ We use, almost exclusively, a cron schedule. If you plan on using the other schedule objects, provided by Celery, please read thru their documentation & the important notes - https://django-celery-beat.readthedocs.io/en/latest/#example-creating-interval-based-periodic-task - about pointing to the same schedule object.⚠️

Celery is a complex topic, so it's a good idea to invest time reading the documentation & understanding the different configuration options.

We constantly do that & find new things or find better approaches to our problems.

About type annotations & using mypy, this tweet resonates a lot with our philosophy.

We have projects where we enforce mypy on CI and are very strict with types.

We have projects where types are looser.

Context is king here.

The way we do Django is inspired by the following things:

- The general idea for separation of concerns

- Boundaries by Gary Bernhardt

- Rails service objects