| layout | root | title | minutes |

|---|---|---|---|

lesson |

. |

Just enough statistics |

25 |

Our RCT attempts to answer a research question by collecting data from a sample of a population.

Data collection consists in measuring the values of several variables for each member of the population.

First, we gain insight into the data we have collected by inspecting it, organising it, summarising it. This is descriptive statistics.

Then, we use the data to draw conclusions about the population from which the sample is collected, and to test the reliability of those conclusions. This is inferential statistics.

Variables may be continuous or discrete.

Continuous variables can be measured with arbitrary precision. Think of the age variable in our dataset: we are measuring it to the nearest year, but in theory we could measure this in seconds, nanoseconds or even more accurately.

In contrast, Discrete variables take only a fixed number of possible values. Look at the random variable in our dataset which only takes the values 'drain' and 'skin', or the satisfaction variable that takes only the values 'Poor', 'Satisfactory'', Good' and 'Excellent'.

NB. The values of random don't seem to have any particular ordering, but the values for satisfaction do: 'Good' is higher than 'Satisfactory', and so on. We therefore call this an ordinal variable. However, are we sure that the distance between 'Poor' and 'Satisfactory' is the same as that between 'Good' and 'Excellent', etc? Maybe not. We should probably conclude, then, that the satisfaction variable isn't interval. It is worth thinking about these things because they affect the tests we can use later on.

Let's think about the age variable in our data can take, and how often it takes each one. We can visualise this with a histogram:

# The 'breaks=20' part dictates how many 'bins' the histogram uses

hist(RCT$age, breaks = 20)

Our RCT dataset contains 64 rows of observations, but imagine if it contained 1 million rows, or even more. We would start to build up a detailed picture of how often different ages occur in our data. This would be the distribution of the age variable. Let's look at a few of the other variables.

hist(RCT$ps12)

hist(RCT$id, breaks = 20)

ps12 could be described as right-tailed, or right-skewed. It might seem a bit irrelevant to plot a histogram for the id variable, but this is a great example of the uniform distribution (where all states of the variable are equally likely). There is another, very important distribution you will also have heard of:

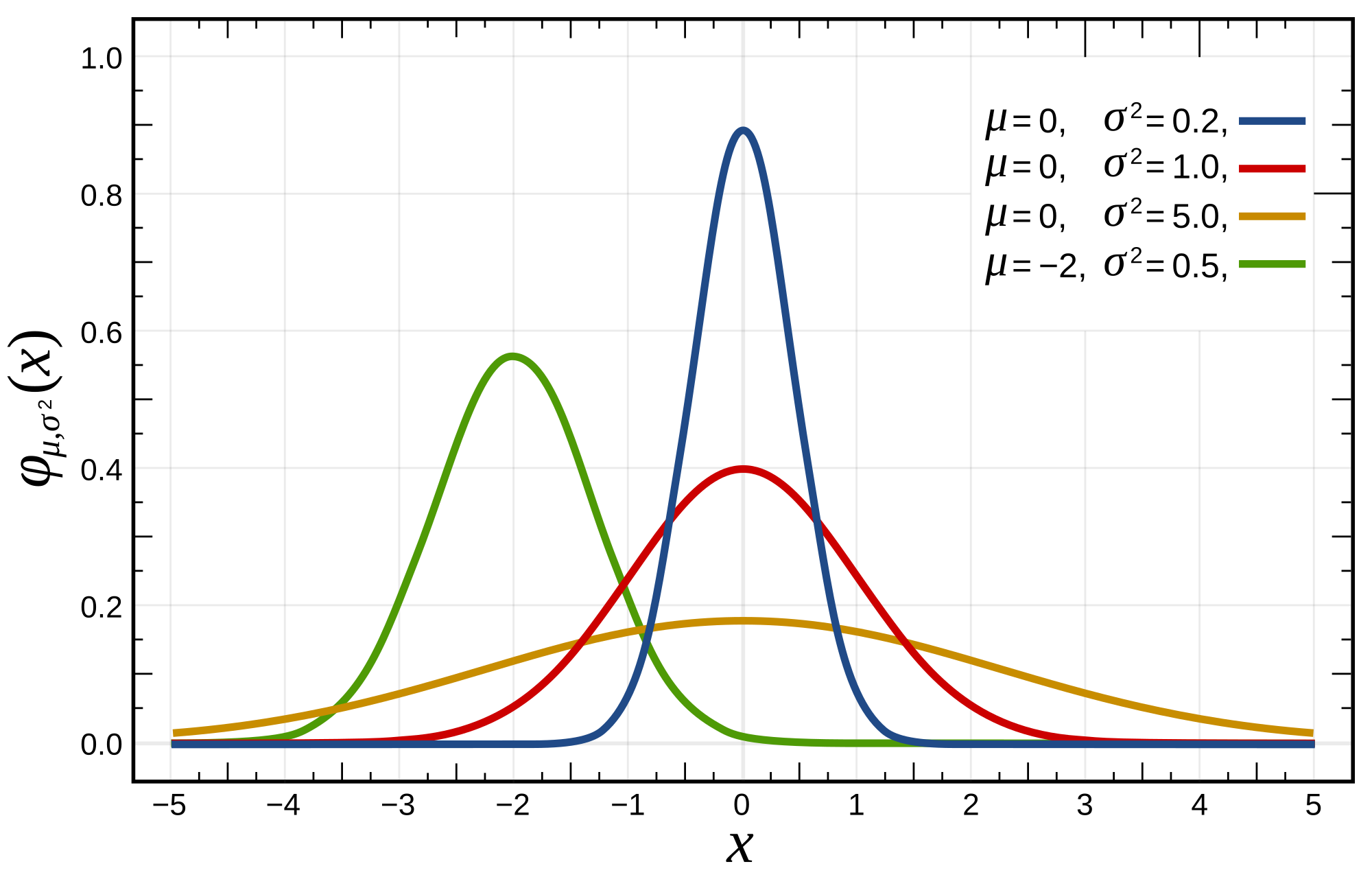

We can see how the centre-point of the bell curve shifts right and left as the mean of the distribution changes, and how the thin-ness or fatness of the distribution alters as we change the standard deviation.

A key question to ask yourself as you inspect the histograms for your data is, does this variable approximate the normal distribution? That is, if we kept taking more-and-more observations in our experiment, would the histogram we obtain look more-and-more like a bell-curve? Again, this is important to think about because if affects the tests we can use later.

It actually turns out that none of the variables in our RCT are normally distributed (age comes the closest, but it is too left-skewed). Let's pretend for a second that the age data were normal:

RCT$fake_age <- rnorm(nrow(data), mean = 50, sd = 2))

hist(RCT$fake_age)

Recall:

- Mean = sum of all datapoints/number of datapoints

- Median = middle datapoint, if all data were arranged in order on a line

- Mode = most common datapoint

Try calculating the mean and median for the following data columns: age, ps12, move24h

You can use the following functions: mean() and median()

For measuring the 'spread' of the data:

- For normally-distibuted data, use standard deviation

- for non normally-distributed data, use interquartile range, i.e if all data were arranged in order on a line, the range between 25% and 75% along this line

You can calculate lots of useful descriptive statistics in one fell swoop using just one simple R function:

summary(RCT)

It's easy (especially using R) to plug numbers into a multitude of tests, and get answers out. However, your answers will only be meaningful if you think carefully about:

- The hypothesis you want to test

- Where your observations come from

- The type of variables you are dealing with

- The assumptions that different tests use

- Interpreting the test results

The best person to advise you properly on the above is your friendly neighbourhood statistician, but in the absence of this we will outline a few simple things for you to think about.

Let's test this hypothesis:

'Patient satisfaction after axillary node dissection depends on whether they received local anaesthetic via the drain or injection to the skin flaps.'

So, our independent variable (the one we are deliberately changing between group) is the random column in our data, and our dependent variable (the one we are looking for changes in) is the satisfaction column in our data.

Think back to your epidemiology lectures and remember that we will technically be testing for evidence against the null hypothesis of no effect:

'Patient satisfaction after axillary node dissection does not depend on whether they received local anaesthetic via the drain or injection to the skin flaps.'

As we said before, random and satisfaction are both discrete variables, so it sounds like using the chi-squared test for independence might be a good plan here. Let's look at a table of just the variables we are interested in.

tbl = table(RCT$random, RCT$satisfaction)

tbl

There are 35 patients in the 'drain' group and 29 in the 'skin' group, and if the null hypothesis is true R can work out what counts it would expect to see in each table cell proportional to this.

Using this test might not be such a good idea after all, as some of the counts in the table (e.g. for those patients who rated their satisfaction as 'Poor') are very low. Intuitively, we wouldn't read too much into data from just 3 patients, and applying a statistical test can't change that. As a rule of thumb, you shouldn't use this test unless you have counts of 5 or over in every cell of the table.

Were we to press on and run the test anyway, it only takes a few keystrokes. Before we do so, however, we should decide what a significant result will look like. Let's use the common, but arbitrary threshold of a p value of 0.05 or lower to constitute significant evidence against the null hypothesis.

chisq.test(tbl)

# X-squared = 2.249, data = 3, p-value = 0.5224

R has helpfully calculated the 'degrees of freedom' and a p value for us, which achieves nothing like significance.

But wait, we said earlier that satisfaction is an ordinal variable. We can use this fact to test our hypothesis in a different way, but first we have to less R know that this ordering exists (if we haven't done this earlier):

RCT$satisfaction <- factor(RCT$satisfaction, levels=c("poor", "satisfactory", "good", "excellent"), ordered=TRUE)

RCT$random<- factor(RCT$random, levels=c("drain", "skin"))

Let's look at the the class-conditional distributions we will be comparing. This is a fancy term for comparing the histograms of the satisfaction variable patients in the 'drain' group vs. patients in the 'skin' group. Note that we have to use the (slightly clunky) as.numeric() function here, to get our data in the right format so that R doesn't get confused.

hist(as.numeric(df$satisfaction[which(df$random=='drain')]))

hist(as.numeric(df$satisfaction[which(df$random=='skin')]))

Judging by eye, it looks like patients in the 'drain' group were a bit more satisfied. Let's test this assumption more formally using a statistical test, remembering that:

- Our independent variable is binary (discrete with just 2 possible values)

- Our dependent variable is ordinal, but not interval

- We are comparing observations from different patients, so we need an unpaired (if instead we were comparing observations from the same patient at different times, we would want a paired test

The Mann-Whitney U test fits well with the above, and we run it like so:

wilcox.test(

as.numeric(df$satisfaction[which(df$random=='drain')]),

as.numeric(df$satisfaction[which(df$random=='skin')])

)

Once again, our p value is under our predetermined threshold, so we shouldn't conclude that there is a significant difference between groups. At most, we see a 'trend towards significance' which might serve as inspiration for a larger study.

A really handy resource for looking up which test to use, and then how to implement it in R, is UCLA Which test?. Another helpful resource is BMJ Which test?.